Why Don’t Dogs Learn from Traumatic Encounters with Wildlife?

Stefanie Schwartz, DVM, MSc, Dip. ACVB

Rattlesnakes, Skunks, Spiders and Porcupines, Oh My! Dogs are often repeat offenders in their contact with dangerous creatures. One would think, from our human perspective anyway, that contact with something so painful and frightening would leave an indelible mark in a dog’s memory. If “curiosity killed the cat” does it apply to dogs, too? From the dog’s perspective, the urge to pursue critters equipped with some of Nature’s strongest defenses often seems to be simply irresistible.

Rattlesnakes, Skunks, Spiders and Porcupines, Oh My! Dogs are often repeat offenders in their contact with dangerous creatures. One would think, from our human perspective anyway, that contact with something so painful and frightening would leave an indelible mark in a dog’s memory. If “curiosity killed the cat” does it apply to dogs, too? From the dog’s perspective, the urge to pursue critters equipped with some of Nature’s strongest defenses often seems to be simply irresistible.

Slow moving, shaggy looking porcupines probably are very tempting to dogs looking for a predatory thrill or just playful curiosity. Back East, dogs seem to run into porcupines more often than they do here on the West coast. Either way, the porcupine usually wins. Porcupine quills are not ejected, they simply embed themselves into the dog on contact; undetected quills can then migrate into remote areas much like foxtails do. Do dogs learn to avoid porcupines following this painful encounter? Nope.

I wonder if a skunk might resemble a funny looking cat to a dog, although the average dog who knows cats can probably smell a skunk long before it gets too close for comfort. It’s not like Nature has done much to camouflage the skunk either. Black and white is quite easily detected to any animal even without full color vision like dogs. Many poisonous creatures have bright colors and patterns that evolved in part to give potential predators an extra clue to keep away. Skunk spray is particularly noxious; the skunk’s specialized anal sacs evolved to defend the skunk. Unfortunately, they don’t work well against motor vehicles. One would think that simple aversive conditioning (skunk = really stinky + burning eyes/nose) would be enough to deter future inspections. Still, we all know and love dogs who go after skunks over and over again. Why do they do that???

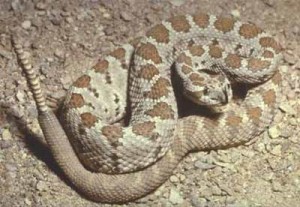

Rattlesnakes usually give plenty of warning before they strike, but they don’t always get the chance. Goofy dogs galloping through the woods or canyons off leash can trample or startle the snakes. What’s a poor snake to do? Dogs just don’t seem to understand the rattler is a warning to stay away, and instead continue to approach within striking distance. There is definitely a communication problem between rattlesnakes and dogs.

Spiders are everywhere and serve as an important part of the ecosystem. Spiders don’t generally attack without provocation unless you’re a fly caught in its web (although females with eggs can have more of an attitude, just like any mother defending its young). Most spider bites occur when the spider is accidentally startled by a dog, but the dog might have gone too close to investigate the spider. Dogs don’t know that the venom of the black widow spider, for instance, is some fifteen times more toxic than a rattlesnake bite. Perhaps someone should tell dogs about this. In their defense, most dogs probably never saw the spider that bit them. Perhaps someone should tell the spiders this, too.

Spiders are everywhere and serve as an important part of the ecosystem. Spiders don’t generally attack without provocation unless you’re a fly caught in its web (although females with eggs can have more of an attitude, just like any mother defending its young). Most spider bites occur when the spider is accidentally startled by a dog, but the dog might have gone too close to investigate the spider. Dogs don’t know that the venom of the black widow spider, for instance, is some fifteen times more toxic than a rattlesnake bite. Perhaps someone should tell dogs about this. In their defense, most dogs probably never saw the spider that bit them. Perhaps someone should tell the spiders this, too.

So why don’t dogs learn to avoid dangerous critters? Well, it’s not entirely clear. But, encounters are more likely in dogs who:

So why don’t dogs learn to avoid dangerous critters? Well, it’s not entirely clear. But, encounters are more likely in dogs who:

- Roam off leash

- Have strong prey drive

- Are young, playful and naïve

- Are not under reliable voice command

- Are not closely monitored during walks

- Are not easily frightened by novel stimuli

Some dog trainers offer training to teach dogs to avoid rattlesnakes. Typically, an electric shock collar is placed on the dog who is then set up to approach a captive live rattlesnake at which point the electric shock is delivered. Shock collars, in my opinion, are not humane and can create more problems. Using rattlesnakes as live bait gives me a big problem, too.

Here are some tips to keep dogs safe from unfriendly neighbors:

- Dog owners should keep their dogs on leash in high risk areas (or avoid these areas completely).

- Keep yards free of habitats (e.g. piles of debris, clutter, over turned flower pots) for snakes and spiders.

- Control rodent population that might attract snakes: don’t feed dogs outside or offer bird seed close to the house (this will also attract other scavengers).

- Repair breaks in your fencing.

- Block access to crawl spaces under your porch, deck or shed.

- Install floodlights in your yard to deter nocturnal creatures from entering the kill zone.

- Make some noise before you let your dog outside so any unwelcome visitor has a chance to get away. Place a strip of jingle bells on your back door, or hang wind chimes near the door. Borrow one of your kid’s noise makers and give it a toot, buzz or clang before your dog goes out.

So here’s the thing: we shouldn’t be asking ourselves “Why dogs don’t learn from their mistakes with wildlife?” The real question is “Why don’t WE learn from our mistakes?” If we persist in setting our dogs up to come in contact with danger, then accidents are no longer accidents. The canine predatory drive is likely to override any learning that may have occurred from previous traumatic experience, but the bottom line is that it is still our job to protect those we love from getting hurt.

© Stefanie Schwartz, 2011